PONV Management and Impact

Learn from your peers about clinical considerations, management guidelines, and the impact of treating breakthrough PONV in the PACU.

The adverse impacts

of breakthrough PONV

In high-risk patients

can experience PONV1,2

can experience PONV despite prophylaxis3,4

In patients who failed prophylaxis

can experience nausea4,5

can experience vomiting4

In a survey of patients (N=220) undergoing preoperative anesthetic examination, more patients ranked PONV as their top postoperative concern than pain (49% vs 27%).10

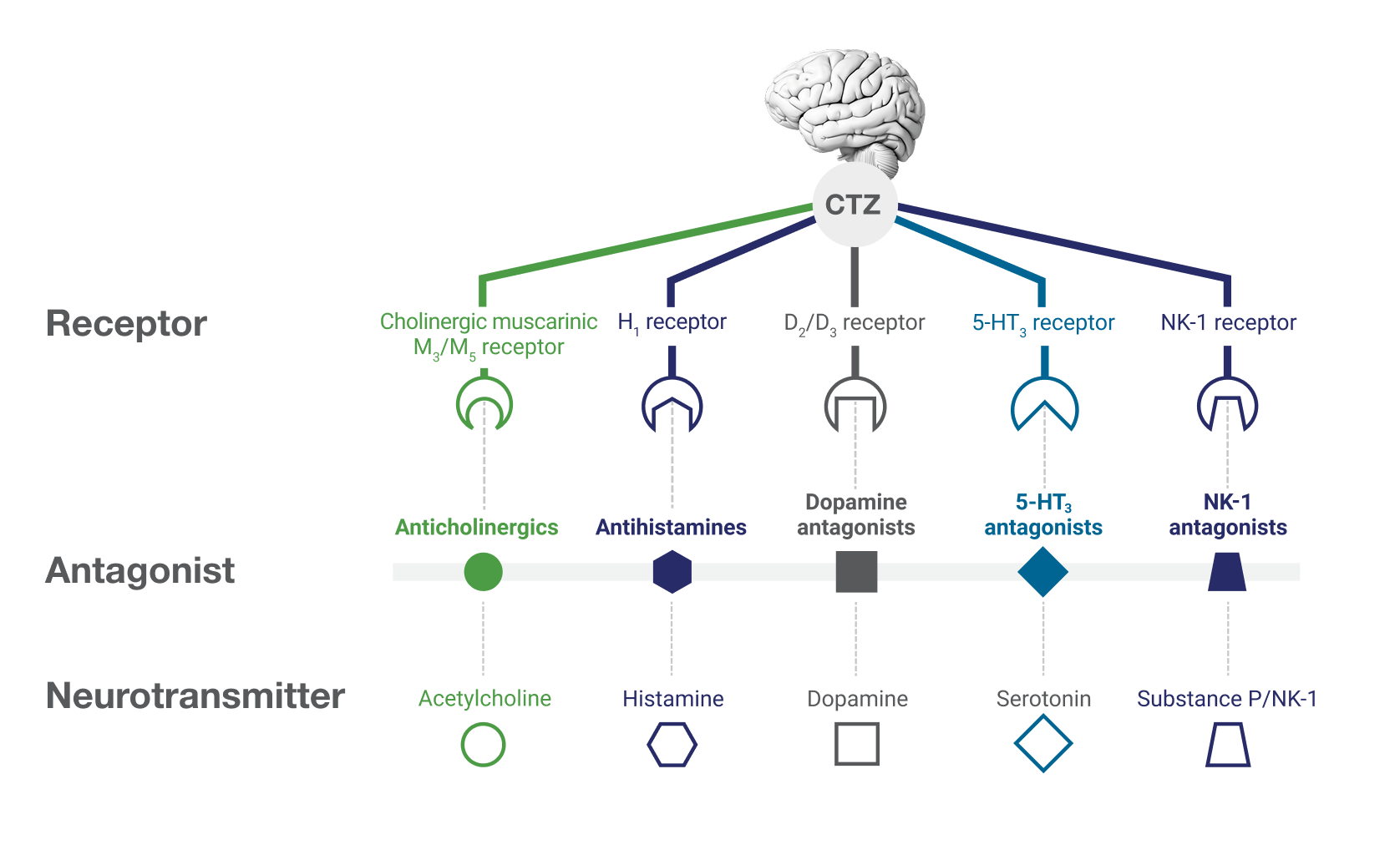

Multiple neurotransmitters and their receptors (eg, D2/D3, 5-HT3, M3/M5) can induce nausea and vomiting.11,12

Therefore, repeating an antiemetic that works on the same receptors as the prophylactic treatment does not improve efficacy.1,13

Quantify the number of risk factors to determine risk and guide prophylactic antiemetic therapy

For patients needing rescue treatment, options may be limited as PONV agents are associated with challenges and undesirable side effects.

Learn from your peers about clinical considerations, management guidelines, and the impact of treating breakthrough PONV in the PACU.

Explore the pathways that trigger nausea and vomiting to enhance your PONV care.

5-HT3=5-hydroxytryptamine type 3. CTZ=chemoreceptor trigger zone. D2/D3=dopamine type 2 and type 3. H1=histamine type 1. M3/M5=muscarinic type 3 and type 5. NK=neurokinin. PACU=postanesthesia care unit. PONV=postoperative nausea and vomiting.

References: 1. Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, et al. Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(2):411-448. 2. Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91(3):693-700. 3. White PF, O’Hara JF, Roberson CR, et al. The impact of current antiemetic practices on patient outcomes: a prospective study on high-risk patients. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:452-458. 4. Habib AS, Kranke P, Bergese SD, et al. Amisulpride for the rescue treatment of postoperative nausea or vomiting in patients failing prophylaxis: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Anesthesiology. 2019;130(2):203-212. 5. Habib AS, Chen YT, Taguchi A, Hu XH, Gan TJ. Postoperative nausea and vomiting following inpatient surgeries in a teaching hospital: a retrospective database analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(6):1093-1099. 6. Golembiewski J, Chernin E, Chopra T. Prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Am J Health-Sys Pharm. 2005;62:1247-1260. 7. Hill RP, Lubarsky DA, Phillips-Bute B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic therapy with ondansetron, droperidol, or placebo. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(4):958-967. 8. Parra-Sanchez I, Abdallah R, You J, et al. A time-motion economic analysis of postoperative nausea and vomiting in ambulatory surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59(4):366-375. 9. Viellette EL, Gonzalez B, Irwin JS, Peters I. Nurse discharge by criteria decreases post anesthesia care unit (PACU) length stay. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021;36:e13. 10. Eberhart LH, Morin AM, Wulf H. Patient preferences for immediate postoperative recovery. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89(5):760-761. 11. Kovac A. Mechanisms of nausea and vomiting. In: Gan TJ, Habib A. eds. Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting: A Practical Guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2016:13-22. 12. Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: its etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162-184. 13. Kovac AL, O'Connor TA, Pearman MH, et al. Efficacy of repeat intravenous dosing of ondansetron in controlling postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. J Clin Anesth. 1999;11(6):453-459.